Morse Believed That Only Portraiture Could Be a National American Art Form

Weastward are living in a celebrated era for public art, when the images that grade our unconscious notions of who we are as a nation are beginning to topple. Around the country, statues whose implicit purpose was to promote racial superiority are being removed and recontextualized. Here in Washington country, the Legislature recently voted to remove its 1950s-era statue of Marcus Whitman from Statuary Hall at the U.Due south. Capitol. The imaginary delineation (no portraits of Whitman be) helped promote a heroic legacy for a missionary whose story was warped and embellished to conform the prejudices of the times. The Washington legislators hope to supersede it with a statue of the Nisqually tribal leader Billy Frank Jr. His fight for treaty rights and efforts to protect the environment are well documented.

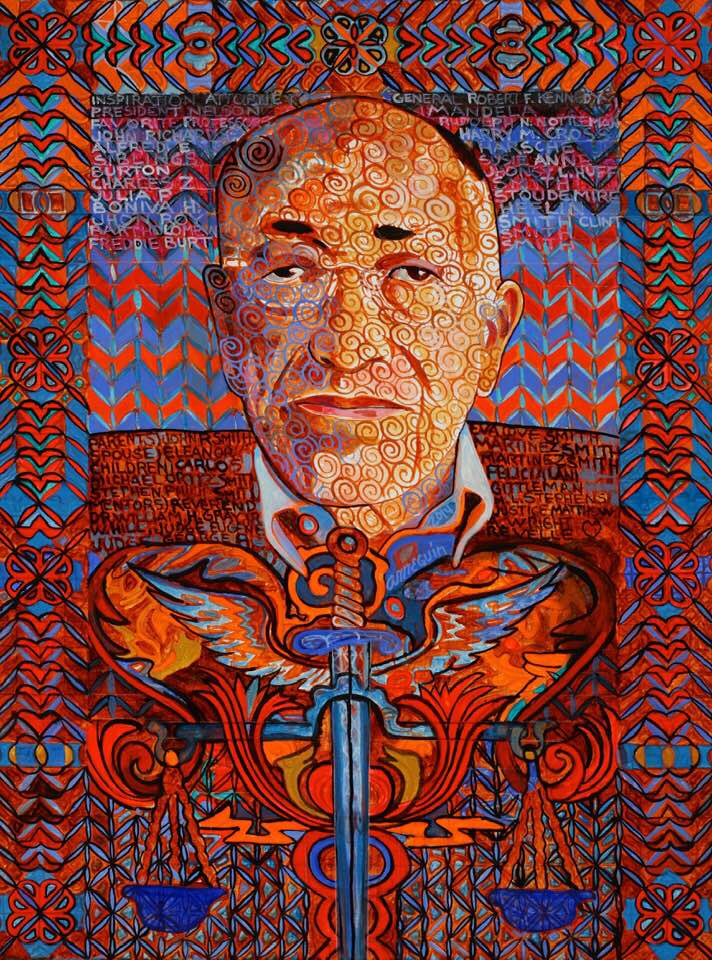

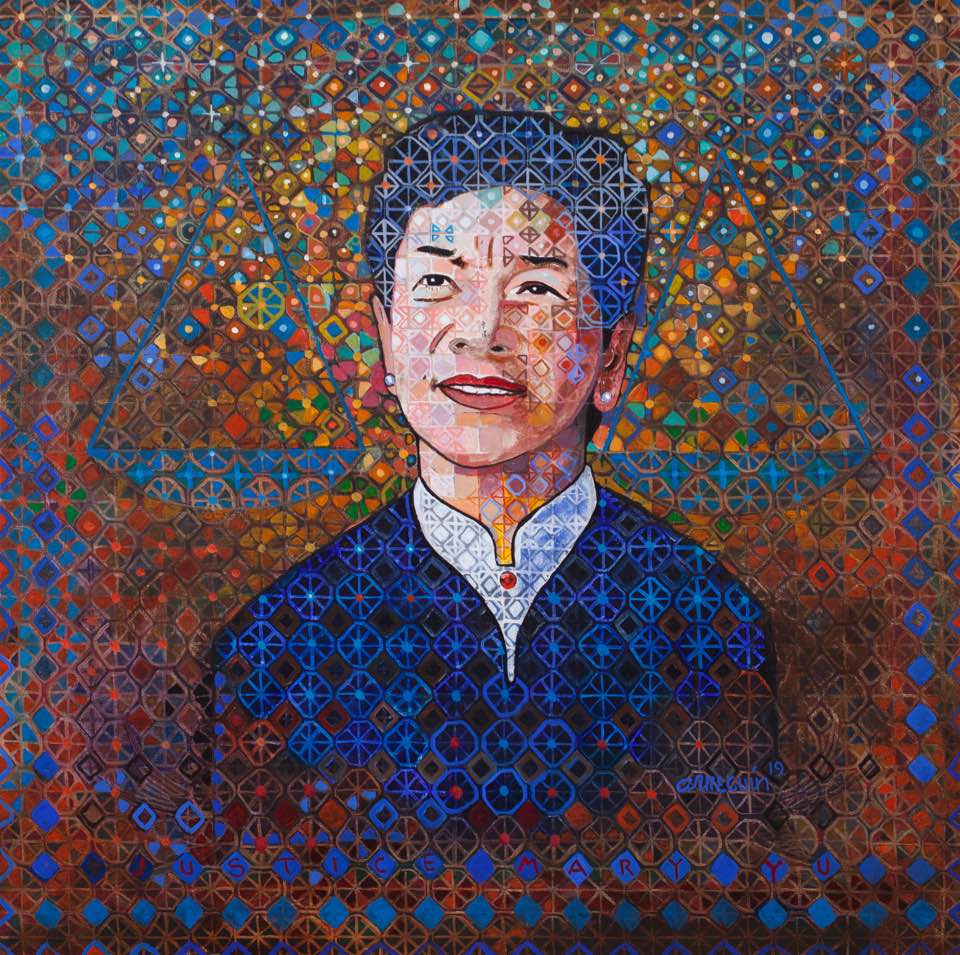

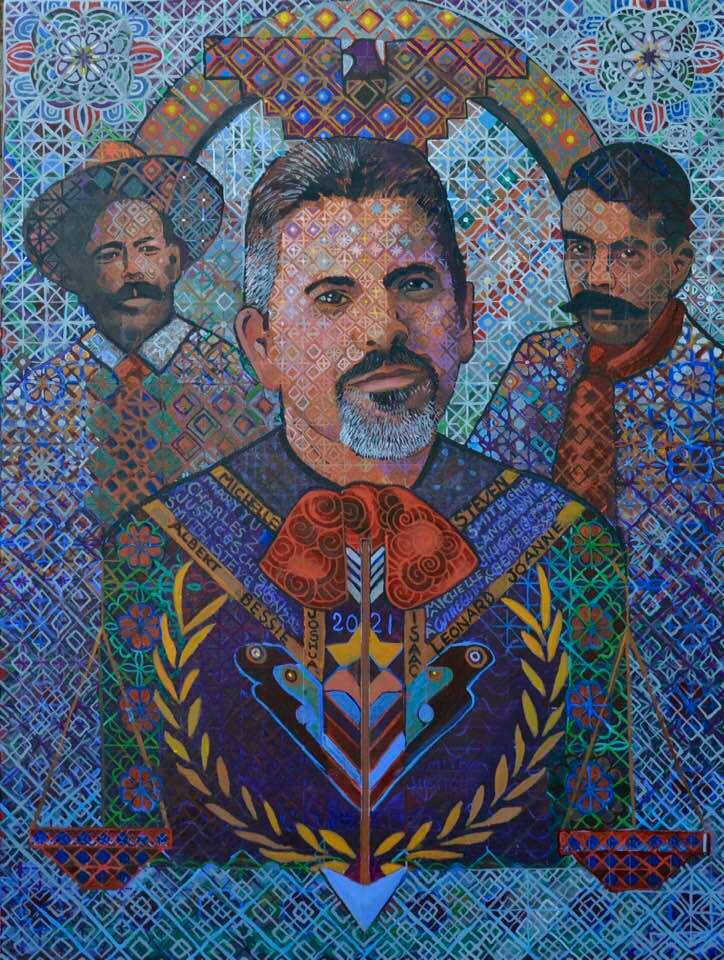

As nosotros correct the misinformation and omissions of history and seek truthful and fair images to replace quondam stereotypes, the Washington country Supreme Court has taken on the issue in its ain Temple of Justice. During the past decade, the courtroom has commissioned prominent Mexican American artist Alfredo Arreguin, '67, '69, to paint portraits of justices of color, beginning with the late Charles Z. Smith, '55, the first African American to serve on the courtroom. More recently, Arreguin completed portraits of the distinguished Justice Mary Yu—the commencement Latina, first Chinese American and offset openly gay justice—likewise as groundbreaking Chief Justice Steven González, the starting time person of colour to serve in that position. Arreguin's intricate, brightly colored paintings help rest the previous lineup of dark-suited white males. But information technology turns out those early portraits all the same have some diversity secrets of their own to reveal.

This story begins in 2011, when Justice González was showing his family around his new workplace at the Washington state Supreme Court. His 7-year-quondam son, looking at the somber portraits of past justices that lined the hallway, surprised him with a question: "Why doesn't anybody expect like united states?" Justice González acknowledged the problem—and vowed to right information technology.

He phoned his friend Arreguin, an internationally recognized artist whose work hangs in the National Portrait Gallery and the Smithsonian American Art Museum. And he asked a favor: Would Arreguin be willing to paint a portrait of Smith, González's mentor and the first person of color and offset African American to serve on Washington state's Supreme Courtroom? González couldn't promise there would be money to pay for the commission, simply he bodacious Arreguin that Justice Smith was a wonderful person and outstanding judge who deserved to be commemorated.

Arreguin agreed, simply hesitantly. He had seen the formal poses and dark colors of the other portraits hanging in the Temple of Justice and told González: "Mine is not going to look like that. Those are like classical music, and mine is more similar jazz."

"Yours will exist Cumbia," González quipped, referring to the exuberant Latin American dance rhythm. That'due south exactly what he wanted.

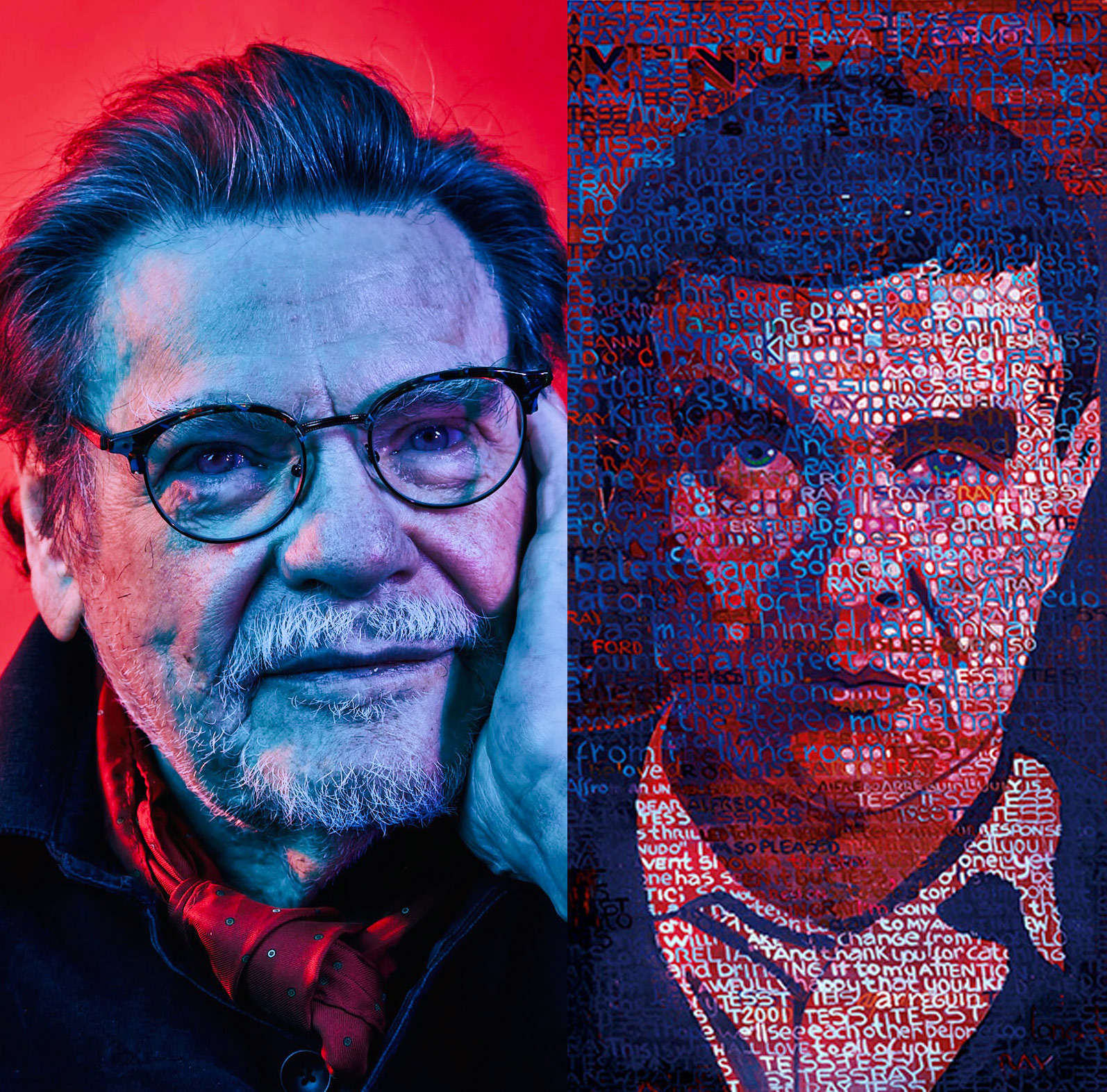

Alfredo Arreguin in his basement home studio in Seattle, photographed past Quinn Russell Brown on June 23, 2021.

Arreguin doesn't think of himself as a portrait artist per se: the people in his paintings ordinarily serve as symbols of traits he admires. In order to draw a living subject, someone with a distinct graphic symbol and attributes, he needed to find a new strategy. The solution Arreguin chose was unproblematic: "I make them my accomplice." When he prepared to paint Smith, "I went to the judge and I said we are going to exercise this painting together, so I want you to tell me all the things that happened in your life, what is meaningful to you. And he sent me a letter, and I used that all in the painting."

Later, when it came time for Arreguin to pigment Yu, the process was not every bit easy. "I was not a willing participant," Yu said. "Portraits: those things are done when you die or maybe when you lot retire. But to have a portrait by such a wonderful artist is really humbling, and I wasn't really thrilled that Justice González had proceeded with this. I was very annoyed with him, in fact."

So, Yu made a condition: When Arreguin arranged for a lensman to take a moving picture of her, she insisted that González have his photograph taken, too. Later, she and the other members of the court agreed it was time that his portrait should be painted as well.

Currently, Arreguin'southward portraits hang in parts of the Temple of Justice that are accessible merely to members of the courtroom and staff. But González has requested permission to take them installed downstairs in the police force library, which is generally open to the public, subject to COVID-nineteen regulations. This leads us dorsum to the question González'southward son put to him. The principal justice says he feels strongly that what's depicted in Arreguin'due south portraits is much greater than the individuals.

"It'southward very important to me and important for kids of color to see themselves represented," he said. "I also desire white kids and adults to see that we are part of this history and presence here too. I recall the classic of what a gauge looks like needs to change, and that changes with imagery and with art and with us beingness comfortable with diversity and difference."

The belatedly Washington Supreme Court Justice Charles Z. Smith, painted by Alfredo Arreguin.

Associate Justice Mary Yu, of the Washington Supreme Court, past Alfredo Arreguin

"Many places with the rule of police force like ours in the Supreme Courtroom still don't have the spread of diversity that we take. And then that is truly extraordinary."

Associate Justice Mary Yu, of the Washington Supreme Court

In that respect, the Washington state Supreme Courtroom stands as an case. Afterwards all, with seven female and 2 male justices of multiple racial and cultural backgrounds, our court is the near diverse in the country.

"In the country, yeah," Yu affirmed, "but some have also said [nosotros have the most diverse court] in the world, and I believe that. … Many places with the dominion of police like ours in the Supreme Court still don't have the spread of diversity that we have. So that is truly extraordinary."

However, every bit Yu points out, not all justices who have served on the court have painted portraits, and there is no system for how they are chosen. The court does commission photographs of each justice and that is where Yu sees modify happening. "I look forrad to the day when there are more people of colour who retire and whose black-and-white pic goes up with the hundred others who take come before us; and that people can see the progressive alter, how it went from male person to female person and people of color. I think that'southward going to be such a powerful statement …"

Truthful plenty. But what nearly all those old painted portraits lining the hallways at the Temple of Justice, of the white men—and they were all men—who served on the court in its earlier days? What should we make of them? How were they caused? I wanted to know who painted those pictures and who maintains them. Are they endemic past the state and office of our public art drove? (Well-nigh are hanging in areas of the edifice that are not open up to the public.)

Arreguin's official portrait of Washington State Supreme Court Chief Justice Steven C. González

Information technology didn't accept long to find out that nobody at the offices of the court, or the police force library housed in that location, or even the longest serving still-living justice, had any idea how the paintings got in that location or when. Nor could the Washington Land Arts Commission help. The judicial branch is its own domain and the artworks at the Temple of Justice are not part of the State drove; they belong to the court.

Eventually, I was referred to a researcher at the State Archives, who managed to observe some data. And what Ben Helle discovered wasn't listed in official documents or correspondence or some obscure piece of legislation.

No: Helle turned to the newspapers. He located a 1915 article in the Seattle Daily Times that detailed the commission of the get-go three portraits caused by the court, two of which now hang in a reception expanse exterior the Chief Justice's office. We now know that the Washington State Bar Association deputed those portraits—of Ralph O. Dunbar, who served from 1889 to 1912 and was the first chief justice; Thomas Anders, from 1889-1905; and James Reavis, 1897 to 1905. Perhaps more than importantly, we also now know that the paintings deserve to be recognized not only for the justices they describe, simply also for the artist who painted them. Ella Shepard Bush (1863-1948), who had an art studio on 3rd Avenue in Seattle, was a rarity at the fourth dimension: a single adult female who worked equally a professional creative person.

Left: Alfredo Arreguin photographed on the back deck of his Seattle habitation. Correct: "Mi Amigo Ray," Arreguin's portrait of Raymond Carver, ane of the most acclaimed American short story writers of the 20th century. Carver's story "Menudo" establish inspiration from Arreguin and partially takes identify in Arreguin's kitchen, where the narrator is comforted by the warm touch of Alfredo. "He put his big painter's hand on my shoulder," the narrator says, lamenting several pages later on that he fell out of touch with his painter friend. Today, 33 years after Carver's death, Arreguin ofttimes tells stories nearly his friend Ray.

Built-in in Illinois, she trained at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., earlier entering the Arts Students League in New York, where she studied portraiture, considered a respectable art grade for women at the time. In 1887 Bush moved to Seattle and opened her studio, where she taught private students, among them the creative person Roi Partridge (1888-1984, husband of renowned photographer Imogen Cunningham) and the author and UW professor Morgan Padelford (1875-1942).

Bush-league also painted portraits of notable Seattle citizens, including Dr. Alexander J. Anderson (president of the University of Washington from 1877-1882) every bit well equally King Canton Superior Court Judges T. J. Humes, Richard Osborne, Orange Jacobs, Charles D. Emery and I.J. Lichtenberg. (Bush's father, information technology turns out, was a lawyer.)

With a picayune more than digging, and assist from my friend David Martin, curator of the Cascadia Art Museum and a specialist in early Northwest artists, I learned that other portraits at the Temple of Justice besides correspond the work of noteworthy and various Seattle painters. Like Bush, these artists exhibited their work nationally and were trained at esteemed academies in the U.S. and abroad. At least two were immigrants (from Republic of hungary and Italy) and one was a prominent Seattle woman painter, Jeanie Walter Walkinshaw (1885-1976), wife of a lawyer and mother of the belatedly Seattle attorney, Walter Walkinshaw. (So as now, it didn't hurt to have connections!)

It'south an interesting twist to this story virtually variety that Bush'south name, as the artist, is not acknowledged at the Temple of Justice. González says that volition change. He plans to have plaques created that evidence the artist'south name as well. The Temple of Justice will soon be closing for renovation. When it reopens, visitors will be offered more than consummate information nigh any paintings in public areas.

I find information technology ironic, likewise, that no information about the artists was recorded in documents at the state archives or the bar association, or in the law library at the Temple of Justice, merely is known to us today because of a story in the daily newspaper. It's a expert argument for the old adage that newspapers are the first draft of history. And with paper staffs shrinking and papers dying off, it's another reason to worry nigh where researchers of the future will turn for data.

Source: https://magazine.washington.edu/feature/alfredo-arreguin-portraits-change-olympias-temple-of-justice-for-the-better/

0 Response to "Morse Believed That Only Portraiture Could Be a National American Art Form"

Post a Comment